|

Buy

Lin Anderson eBooks at the |

Buy

Lin Anderson eBooks at the |

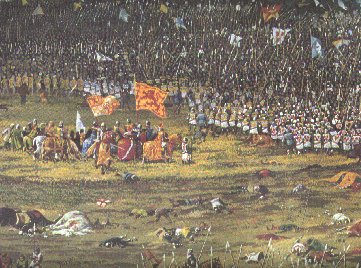

Bannockburn

Battle Sequence of Events

|

|

|

Siege of Stirling and the pact with Mowbray

In the year 1314, after 18 years of war, Scotland north of the Forth was free. Stirling, one of the few castles still held by the English lay under Scottish siege. Edward Bruce, the King's brother, lacking in siege equipment, had remained their for many months in the hope of starving the English out. Sometime in the spring though, Edward, in the chivalry of the time, made a pact with the castle's governor, one Sir Philip Mowbray. It was agreed that if an English relieving force had not arrived by midsummer's eve, the castle would be surrendered to the Scots. Robert, on hearing of this was furious with his brother. So far he had relied entirely on guerrilla tactics to oust the English, and undoubtedly Edward II would send a force north, which would mean a pitched battle if Stirling was to be saved.

Edward II, on hearing this news was only too happy to oblige, deciding he could finish his father's work in one huge thrust. He amassed an army of some 40,000 men with the intention of crushing the rebellious Scots once and for all, so finally putting and end to the dispute.

His army was an enormous one, even by medieval standards. It included some 2,500 heavy cavalry, 2000 Welsh bowmen and 500 light cavalry, with the rest consisting of highly trained infantry. Edward felt openly confident that the might of his powerful army would easily overwhelm the Scots, who numbered only some 13,000. Following this army, Edward had a huge train of equipment and supplies, which included weaponry, siege engines, foods, wines, and the riches of the Knights and Barons. To watchers, the sight of a column of such splendour marching past must have been magnificent.

Edward had his army muster at Berwick-upon-Tweed. From there, some two weeks before the deadline, they crossed the border at Coldstream, and marched north to Stirling.

On the 23rd of June, midsummer's eve 1314, the army of Edward II arrived before the Bannockburn ford.

As Robert Bruce had anticipated, they had come by the old roman road, so he had set his positions accordingly, his divisions lining the road under the cover of the forest. For him to win he would need to fight the battle on his terms, which meant confining the bulk of the English army to a gap to small for them to fight at full force. He hoped then that his schiltroms* could repel the thrust of the English cavalry, keeping his lines unbroken.

For the battle site, Robert had chosen the narrow gap between the woods surrounding the Bannockburn village and those on Gillies Hill, near where the road fords the Bannock Burn. Within the woods he blocked all paths with branches and dug pits which he covered with sticks, anti-cavalry traps intended to counter an outflanking movement. Then with his men in position, he waited.

* A schiltrom was basically a large circle of men who carried huge 15 ft pikes. They were trained to march consistently in this formation with pikes outwards, forming an impenetrable wall of spears.

On the arrival of the English, Stirling's governor, Sir Philip Mowbray rode out to meet Edward. He pleaded that a force should be dispatched to relieve the castles garrison, to which Edward agreed, giving him 500 cavalry.

Mowbray knew the Scots positions would make using the road impossible, so he led the force, under Sir Clifford and Sir Beaumont along a narrow bridle path leading from the village to the castle. Within the gorge, which the path followed, the English Knights were well hidden from the Scottish positions. Luckily, just before they had managed to pass, Robert spotted them and immediately dispatched Randolph to intercept.

Randolph quickly gathered his men and charged down towards the English, blocking their path. He knew that there would be no option but to fight, as the English were 500 horse, and would be confident of breaking the Scots lines. So, as the English cavalry gathered for the charge, within the Scots schiltrom spears were grounded and muscles strained in preparation for their impact.

The first wave of cavalry hit the Scots with tremendous force. Their lines held sure though and many English Knights crashed to their deaths on the wall of spikes. The cavalry retreated, gathered and charged again, but still they could not break through. This continued for some time, each charge weakening as more knights fell, their own dead blocking their path.

Meanwhile James Douglas, concerned for Randolph's men persuaded Robert to let him take a small division of reinforcements down to the battle. On arrival though he was greeted by a surprise; it was not the Scots who were failing, but the English, who had given up charging and had now resorted to throwing their hand weapons at the Scots, though to little effect. So Douglas, seeing that it was Randolph's fight, and almost won, held his men and watched as his friend finished the English himself.

The English cavalry began again to retreat, and gathered a small distance from the Scots schiltrom. Suddenly the Scots, confident now of victory, did something before unheard of in medieval warfare, they charged the cavalry. For the English knights this was the last straw. Tired and disorientated, they now found themselves swarmed by the Scottish infantry and in a blind panic began to scatter. Of the 500 English Knights who set out to Stirling, only around 400 struggled back to the camp. As for Scots loses, Randolph reported only 6.

This victory, though small in the fact that they were still outnumbered 3 to 1, elated the Scots. Although they knew the worst maybe still to come, their victory would not only demoralise the English, but prove undoubtedly that a well disciplined schiltrom was capable of repelling heavy cavalry.

James and Randolph returned, taking up their positions again within the Scots lines. On their arrival however, they were to be greeted with the news that Randolph's men were not the only ones to have seen some action. There had also been some skirmishing on the battle front, where The Bruce's division were in position. These skirmishes had been sparked by an incident which was undoubtedly the tensest moment of the entire campaign for The Bruce's men, but with which any Scot with a knowledge of the King remembers with pride.

The main bulk of the English van had crossed the Bannock Burn and taken up position facing The Bruce's division. A young English Knight, one Henry De Bohun, spotted a lone figure riding back and forth along the Scots lines. Moving closer, he noticed that the man carried no crest upon his helmet, but a crown. Seeing that it was none other than King Robert himself, Bohun realised in his quest for glory, that he could end the battle in one go.

Moving from the English lines De Bohun, fully armoured and riding a heavy cavalry horse urged his beast to a gallop, and lowering his lance he aimed straight for the King. Robert, armed only with a battle axe and on a smaller horse, held his ground however until the last second. Just before De Bohun hit him, Robert quickly moved his horse aside and in one blow split open both the young knight's with his battle axe.

The Scots gave a sigh of relief, many shouting about how senseless Robert had been in endangering not only his own life but the future of their cause. The King however replied only with a complaint to the fact that he had broken the shaft of his favourite axe, which rather annoyed him.

This incident obviously could have had horrific consequences if The Bruce had been killed. It would have left the Scots both leaderless and Kingless on the eve of battle, probably putting to an end their long struggle. Luckily Robert remained entirely unscathed to the great relief of his men.

That night, after further small skirmishes along the front line, the English retired and made camp upon the carse, some distance from the Scots lines. For Robert, it was a time to make some very important decisions. From past experience, he knew that because of the small size of his army, to beat the English he needed to fight them at his chosen location, preferably a place where they were confined to a small front. Robert had originally intended this to be between the forest of Gillies Hill and the Bannock Burn gorge. Now that Edward's army had camped upon the carse, the battle would inevitably have to take place on the flat field that stretched down from the road towards it. This meant that the battle front was to be much larger than Robert would have liked. The only benefit to this site was the small gorge that lay between the carse and the field. Although it was not particularly deep, it's sides were steep and it would be a slow process for the large English army to cross safely. Robert knew that if he could attack the English as they were still crossing, he might be able to drive them back upon their own men still trying to cross the gorge. This would cause confusion and disorganisation among them, exactly what he needed.

Later that evening a young Scottish Knight, deserting the English side, rode into Robert's camp and asked to speak to the King, telling him he wanted to change his allegiance. The King, always happy for new recruits, especially from his enemy, accepted and let the man pay homage. With him the knight also brought news, apparently the English had been very demoralised by the events of the day and many were unhappy with young King Edward's command. For Robert, this was the final factor in his decision. He spent the evening discussing the matter with each division in turn, and asked their opinions. For him, unlike many commanders of the time, the thoughts of his men were as important as his own. And to the main question, would they follow him and fight, he was given a resounding "yes".

Main Battle - 24th June 1314

At first light the Scots were already in position. Looking down towards the carse they could see the English hurriedly preparing for battle, with the first of their cavalry making it's way across the gorge. Robert gave one final address to his troops before they were given their church blessing. Edward, watching the Scots kneeling in prayer, laughed aloud believing they begged for his mercy. A wiser man then told him; yes, they did beg , but not to him.

Soon the main bulk of the English van had crossed the gorge and had formed up in preparation for the charge. Robert then ordered his troops to move out from the trees, and gathering into their schiltroms, they took up position to face the onslaught. Within the English cavalry their was confusion however, with two commanders arguing over who was to lead the charge. One called for an advance and rode forward, but was only followed by a few, the rest of the cavalry, momentarily confused struggled to follow.

The impact as the English horse hit the schiltroms was tremendous, but the Scots held. Many of the English knights, charging unorganised, were killed outright on the Scottish pikes, others fell or were dragged from their horses to be crushed by their own men or killed by the Scots.

The lack of English organisation was now becoming horribly apparent to them. Most of their archers were now across the gorge and in a panic someone had given the order to fire. Unfortunately for them, not only were they hitting the Scots but much of their own retreating cavalry. The archers were bad news for the Scots, who no longer had the cover of the trees, but Robert had planned for this. As soon as he gave the signal, Keith the Marischal of Scotland, commanding some 500 mounted infantry charged out of the woods and routed the archers from the field.

With the cavalry retreating, and the archers scattered, there was huge confusion among the English ranks. The Scots, seeing this lifted their pikes and slowly advanced, in perfect formation, driving their struggling enemy back towards the gorge. What remained of the English cavalry continued to retreat and charge, each time being beaten back by the wall of Scottish spikes. With the Scots forcing those who had reached the field further and further back towards the gorge, and at the same time the main bulk of the English infantry still trying to cross, those who were retreating were blocking those advancing. The English army's fate was sealed.

The schiltroms pressed on, pushing more and more men into the horrific crush the gorge had become. Horses and men tumbled down the sides tripping over each other until, as one witness described it: "bodies lay so thick a man could cross the burn dry-shod".

Soon almost all of the English, most not even given a chance to fight, were scattering. Many drowned as they tried to cross the Forth, others were killed or crushed by their own companions in the mad race to escape. Those still left fighting on the battlefield were few and Robert, seeing the victory was theirs gave the order to break up and give chase.

Sir James Douglas, spotting the escape of Edward was given permission by Robert to follow. The young King quickly reached the gates of Stirling but no matter how much he pleaded, the governor Philip Mowbray refused to let him in. Mowbray argued that he must hold his part of the pact as the Scots had been true to theirs. With Douglas on his tail, Edward had little time to argue so gave up and set off south. After many days of hard riding, made worse by Douglas happily picking off any stragglers of the Kings party, he eventually made it to Dunbar Castle. From there a ship took the English king, thoroughly beaten and humiliated, back south to England.

For the Scots, the battle was undeniably one of the greatest in history. Their King, who for 18 years had fought for a cause once thought impossible, had led them to victory. Edward may have had the military might of all England behind him, but in the end it was no match for an army of freedom fighters distinctly lacking in blue blood.

Bannockburn

Battle Site Map | Bannockburn Battle page | BraveClans

MacBRAVEHEART

homepage

|